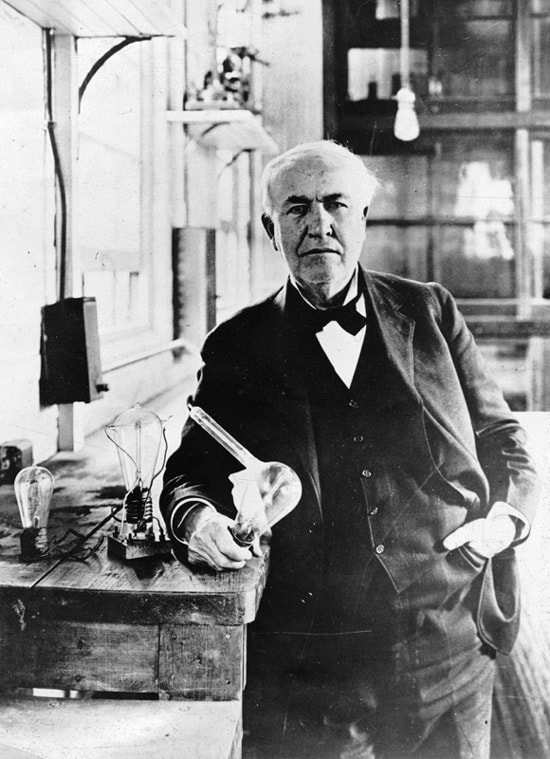

I recently finished Edmund Morris’s epic new Thomas Edison biography. It took me a while to get used to his reverse chronology structure (he works backwards from Edison’s later years to his earlier years), but once I did, I found it riveting.

One thing that caught my attention from the book was the degree to which early 20th century Americans were exposed to rapid technological change. We think the arrival of the internet and smartphones were a big deal, but these innovations were trivial in magnitude compared to the arrival of electricity.

Constraints that had been constant throughout all of human history — the darkness of night, the slow pace of information dissemination — were obliterated in just a few decades.

Edison was born in an age of horses and sailing ships. His death was broadcast worldwide via radio waves, and whole cities — their streets clogged with cars and their skies blotted with steel-girded buildings — temporarily powered down their ubiquitous electric lights to honor his passing.

These changes naturally led to some reactionary technophobia (though, as I argued in a recent op-ed for WIRED, there wasn’t as much of this resistance as popular commentators like to imply). I’m interested in this historical moment of technophobia, as skeptical technology commentators such as myself, or Tristan Harris, Jaron Lanier, and Douglas Rushkoff, are sometimes associated with this tradition by our detractors.

But does this analogy hold up?

There are two problems with connecting the types of ideas discussed in books like Digital Minimalism to Edison-era technophobia.

The first is that many of the anti-technology voices from the early 20th century were disturbed in large part because they didn’t understand the new technology (a new phenomenon in a world in which tools had always before been physical and intuitive). Electricity seemed wholly mysterious and borderline occult.

Modern technology skeptics, however, tend to instead be technologists who are thoroughly familiar with new innovations. I trained in MIT’s Theory of Distributed Systems and Network and Mobile Systems groups: it’s hard to tag me as baffled by the operation of a modern social network or broadband wireless internet.

The second problem is the Edison-era technophobes tended to reject the entire program of new electrical technology as bad. The whole movement scared them, and they wanted nothing to do with it.

Modern skeptics such as myself, Lanier, and Rushkoff, by contrast, have been internet-boosters since its earliest days, and still hold semi-utopian visions about how internet technologies can improve the world. It’s hard to tag us as scared of change in a field where we’ve consistently supported positive disruption.

A better analogy from the time of Edison is his own battle against George Westinghouse to determine whether alternating current was superior to direct current for municipal energy generation. No one at the time thought Edison was anti-electricity or scared of change. They instead recognized he was debating what direction was best for this particular technology’s advancement.

This is the generous interpretation I give to my own critiques of social media. I love the internet, but worry that trying to consolidate it under the control of a small number of Orwellian conglomerates is a costly detour, impeding instead of promoting its advancement. Lanier, Rushkoff, Harris would almost certainly say something similar.

This doesn’t mean we’re right (Edison was wrong in his preference for direct current), but it also doesn’t mean that we were somehow duped by an ill-informed moral panic.

To summarize my take away from studying the life and times of Thomas Edison, be wary of confusing technophobia and techno criticism. The former is not as common as we like to think, and the latter has always been absolutely crucial — especially when delivered by fellow technologists — in the quest to unlock more and more human potential.

Now if I could only figure out how invent the 21st century equivalent of the light bulb…

I found it interesting that you used the phrase “positive disruption.” What’s the most recent example of this that you’ve noticed and supported?

The internet has among many other things: (1) radically democratized the ability of people to both spread and consume information (25 years ago, I couldn’t have the built an audience like I did here over the last 13); (2) enabled essentially free text, voice and video interaction over great distances; (3) is in the process of creating a fluid cognitive remote labor market, which has its disadvantages, but also some huge efficiencies and advantage; etc.

I think the detractors are the ones who doesn’t understand or don’t want to believe the damaging effects of social media. Thanks to Lanier, Rushkoff, Harris and you for spreading the facts.

I love how you distinguish between technophobe and techno criticism. As an EdTech person, people are often confused when I recommend the Digital Minimalism book, as if I’m not allowed to be a minimalist because I teach technology for learning. When in reality, it’s better if I am very discerning with which technologies we use in the classroom. In fact, I’ve become quite the techno critic the more I’ve studied learning technologies.

Question: I know Lanier and Rushkoff, but which Harris are you referencing? Is it Sam Harris?

Tristan Harris

I’m an instructional designer myself, and nobody in the office (or institution for that matter) understands my not having any social media, having a cheap Pixel 3a with almost nothing on it, using Google Fi as my provider, etc.

We fear what we shouldn’t and don’t fear what we should? I’m more entranced by each generation’s willful refusal to learn from those who came earlier. And so we can similar mistakes over and over and over and…

Thanks for this informative post. Looking back and forward can give so many great insights.

Fun fact: Thomas Edison actually drove the Film Industry to Hollywood.

> The second problem is the Edison-era technophobes tended to reject the entire program of new electrical technology as bad. The whole movement scared them, and they wanted nothing to do with it.

Thanks for sharing this point.

I found a person who also share this strange point of view:

“To the electron: May it never be of use to anyone”

? J.J. Thompson

Hi Cal,

I am listening to your interview on the Rich Roll Podcast, and I was wondering about one thing you said: you said solitude is the absence of input from other minds, however you said “unless it’s music”. I am interested to know why you don’t include music in this category? Do you think there is a difference if the music contains lyrics or not?

Sorry, I know this question isn’t related to your article, but would love to hear your thoughts regardless!

All the best from Germany!

Interesting post as usual Cal. Although it’s your last comment that stands out:

“Now if I could only figure out how invent the 21st century equivalent of the light bulb…”

It sounds so simple. I wonder if Edison knew the impact of his invention before it became a reality?

He probably thought to himself one day “Huh, I can use electricity to make light… that’s pretty neat.”

Berners Lee probably thought to himself at one time “HTML, yep, this could be a nice easy way for my colleagues and I to communicate our research to each other… that’s pretty neat”

If most world altering solutions were so obvious, I think they would be invented a lot quicker. Probably most people at the time just lived life, and went to bed after sun down, and probably thought nothing of it.

Edison was very much aware of what he was doing. He did not, contrary to popular belief, invent the electric lightbulb. What he did was invent the PRACTICAL electric lightbulb. Versions existed in his time, but they burned out quickly, or were dangerous, or otherwise were unsuitable for widespread use. Edison was one of the first (the history is a bit cluttered, and getting more so as people push various agendas) to make the lightbulb something people can use.

Ford was similar. He didn’t invent the car–versions had existed for a long time, in fact, before he made his first vehicle. What he did was invent the practical car, one that most people could own and which was relatively easy to use.

In that light, I’d say that the modern PC and tablet are the closest thing to the lightbulb. Neither invented the computer; what they did was to make the computer widespread and easy enough for most people to use.

For my part, I want to know what the equivalent of artificial refrigeration is. Artificial refrigeration hit our society like a nuclear blast, only constructive instead of destructive. It fundamentally altered the way we think of food, and revolutionized medicine, manufacturing, and scientific investigation, to say nothing of transportation. Yes, ice boxes existed, but they were expensive, finicky, and of very limited use. Of all the inventions of the past 200 years, I think artificial refrigeration has had the greatest impact on society.

The thing that kicked off Edison’s interest in the light bulb was encountering one of the first large steam-powered dynamos. The vision that got him, and the investors who quickly backed him, excited was the “sub-division” of light; that is, the ability to have a centralized power generation station that could power many different light bulbs. To make that happen, he had to solve tons of problems around generating and distributing power; he also, as one item on that long to-do list, figure out how to make an incandescent lightbulb that lasted a long time. He did all of it in parallel…pretty amazing