One of the key elements of my deep life philosophy is its emphasis on craft. This topic applies to both professional and leisure pursuits, but in this post, I want to focus on the former. (See Digital Minimalism for more on the latter.)

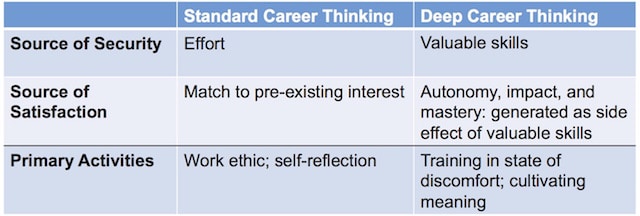

I became really interested in career development ideas around 2010, when I began the research for what eventually became my fourth book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You. Here’s what I discovered about the standard career thinking embraced by many college-educated young people in our country:

- It understands jobs to be like a contract: you do the work assigned, you get to keep the position.

- It believes career satisfaction results from finding the right job for your natural pre-existing interests. This mindset is summed up by the ubiquitous advice to “follow your passion.” If you don’t like your job, it’s because you chose the wrong field.

The deep life philosophy offers an alternative vision centered on valuable skills:

- It believes security comes from being able to do things that are valuable, and, more generally, being comfortable picking up new valuable skills quickly when circumstances require.

- It believes that satisfaction comes from some combination of autonomy, impact and/or a sense of mastery, which (as I argue in So Good) require valuable skills as a necessary precondition.

If you subscribe to standard career thinking, you focus on work ethic; implicitly believing that if you tell people enough times that you’re “busy” when they ask how you’re doing that this will somehow alchemize into indispensability. In times of plenty, you also expend a lot of energy pondering whether your current work is really your “passion,” and daydream about job shifts that might unlock a torrent of latent satisfaction. (Such thinking, naturally, is suppressed during times of economic strain.)

If you subscribe to deep career thinking, by contrast, you focus intensely on training high-value skills, like an athlete looking to maintain an edge. Skills not only provide you security (effort, relatively speaking, is abundant, while there’s always a demand for value-producing expertise), but they can be used as leverage to gain more autonomy, or increase your sense of impact, or provide that powerful feeling of fulfillment found only in mastery: all of which will make your work more satisfying.

Those who lead a deep life, however, also tend to seek ways to boost the meaning they derive from their work. Both dedicated teachers and career military professionals, for example, are known to cultivate well-justified structures of deep meaning around their craft. (I admire both these groups immensely.) While those engaged in purely intellectual pursuits, like professors and writers, often seek inspiring physical environments in which to work.

This is the deep approach to work: Master a useful craft, use this mastery to shape your working life in a way that’s both secure and satisfying, then look to build structures around your efforts that further amplify their meaning.

I only wish this was as easy to do as it was to explain…

Yes, getting from a standard career to a deep career has many ups, downs, twists, and turns along the way. This was a great and timely post. I would love to see a actionable ‘template’ for how to make the transition from a standard to deep career.

Hi Cal,

When faced with intellectual effort, there is the sheer psychological sensation of discomfort and strain. Along with this comes an emotional wrapping that steeps the plain experience, and with a tint that is often negative: “This is not rewarding, this is not right, I’m frightened at making so little progress or going forward so slow etc…” This can then too easily lead to the conclusion of a mismatch between an intrinsinc self and a type of activity : “this feeling of unease is not normal, expanding and growing according to my true inner natu,re should be blissful flourishing rather than tedious toil etc…” And this leads in turn, as you mention, to the hopeless search for the “perfect match”… I’ve fallen for this myself way too many times, and I think the key to avoid it would be to attach an alternative emotional hue to the sensations of effort. Something along the lines: “This sensation of effort is a sure clue that growth is taking place. Healthful growth are tightly linked everywhere in nature. The absence of effort would only mean that an acquired habbit is operating. Life is expanding, as it should”

I guess a concise way to put it would be: if you seek for the view from mountain top, expect uphill hiking, whichever peak or trail you choose…

Thanks for your books that have been sound influences,

Quentin

I like the following rule of thumb: if you’re comfortable with your work, you’re not improving.

Discomfort as in short periods of strain while doing deliberate practice? As long periods of strain and discomfort could lead to burnout. In Dr Barbara Oakley’s Mind for Numbers, she suggests that if study sessions become too frustrating then it is a good idea to take a break as those set of emotions hinder cognitive performance, I suppose there is a healthy amount somewhere in between?

Deb, that is my understanding, yes. One way I’ve seen Cal do this is by taking walks during which he works a difficult problem. These walks act as restorative (and often quite productive) breaks in Cal’s day. He also suggests in Deep Work (I can’t remember where) that our capacity for sustained deliberate practice improves as we go.

I can’t help but wonder what you think of the current economic downturn, and if your views happen to align with financial independence. (I’ve personally found a lot of overlap between your craft-focused approach to work life, minimalism/simple living, and FIRE. They all seem part of the deep life to me – focusing on what’s important, over working on or buying what is frivolous.)

I suspect a lot of people with valuable skills in a good market will find that their skills are no longer valuable in this market. Pilots, for instance, hone a highly technical and valuable skill in general. But with travel down, they suddenly find themselves at a loss. But having money set aside & having a fulfilling life outside of career, they can float along until they are next needed again.

I do find resonance with many ideas from the FIRE crowd. Mr. Money Moustache blurbed my last book…

There are certain tasks that I have performed many times, but I am still not comfortable with. Am I still in some kind of learning curve? Because I always do the tasks well. This kind of bugs me. I figure I should have it down to a lot less discomfort by now. Any suggestions are welcome.

Delve into your emotions and figure out precisely where the discomfort is.

-Are you bored? So good, that someone else should be doing that task?

-Are you befuddled? Doing it well but do not know how to do it better? Break it down and see what you can improve on or get an outside point of view.

Fundamentally it sounded like an emotional question, and clarifying those emotions for you opens the door to the next skill you can develop.

I wonder whether the pursuit of valuable skills in deep career thinking is job-dependent. The jobs you mentioned at the end—teachers, professors, writers, military professionals—are all leadership and/or high-freedom roles. Maybe the hidden caveat is that you must devote enough time to developing skills to reach such desirable jobs. Only then can you see the forest from the trees, the cutting edge from the run-of-the-mill. Otherwise, there is no time to step off the treadmill of tasks that you *must* complete in an ordinary job—do you dare tell your boss that the task isn’t meaningful enough?

Put another way: the college student is inundated with assignments from professors because they’re inexperienced and don’t know which questions are valuable to study. The postdoc, however, has spent an entire PhD chasing after the wrong questions until they finally learned how to ask the right ones. Good postdocs are qualified to become professors because they have a highly developed research taste, giving them a bird’s eye view of their field. These two types correspond to career thinking and deep career thinking—the key difference is that the latter is able to work autonomously because that’s what they were trained to do.

So my question is, should everyone aim to reach the equivalent of PhD-level expertise in their careers? Can the undergrad-level workers earn the freedom to decide which tasks are worthy enough to perform?

Hi Cal,

Can you provide a definition of the term “useful craft” in the context of professional pursuits? How can one measure the utility of his craft/job?

These are questions that I am deeply thinking about for a long time now, but I would appreciate your thoughts on this topic.

Thank you,

Giorgos

Hi Giorgios,

My understanding of a ‘useful craft’ is one that requires rare and valuable skills. And this is applicable to any domain in my opinion. There are a myriad of carpenters that can do a kitchen for you, but most probably you end up with only a handful if you consider the ones that can actually combine sturdiness with aesthetics. The same line of thought applies to knowledge workers as well.

This is right. Rare and valuable are usually the two most important attributes of a useful craft.

Cal,

Succinctly stated. This post is one to which I will refer more in the future.

Thank you for the wonderful article Cal. Your work has been tremendously helpful in my own career path. Appreciate it.

A rousing manifesto.

Reminds of the sense of empowerment I felt when I first started reading your blog Cal.

“Hone a valuable skill”

The last part sounds a bit abstract.

> Both dedicated teachers and career military professionals, for example, are known to cultivate well-justified structures of deep meaning around their craft. (I admire both these groups immensely.) While those engaged in purely intellectual pursuits, like professors and writers, often seek inspiring physical environments in which to work.

Do you mean the career military professionals take pride in their work because they are proud of the belief that they are servicing their country and protecting the people, and that is the “deep meaning” that they cultivate? But there could also be others that say they are part of a war machine that destroys and kills, especially if they are actually deployed to places like Vietnam or the Middle East. I find this example to be slightly weird.

And what’s the relation between “seeking inspiring physical environments in which to work” and “cultivating structures of deep meaning”? This also feels a bit elusive to me.

Great post, as always. I just got a bit confused over this last part. I tried to search in the book but also couldn’t find related content.

I’ve elaborated on these points in my two follow-up posts…

I’m wondering to what extent one’s passion has a bearing on the skillsets they should pursue? As there is a multitude of skills that lend themselves to mastery and therefore meaning, shouldn’t one’s “passion” be a directional component in determining which skillsets to seek out and master?

It seems like the level of interest someone might have for, say, being a photographer would inform the kinds of skills necessary to succeed, flourish and find meaning even if the initial “passion” was oriented around becoming the next Annie Leibovitz and the photographer ends up finding greater meaning in graphic design. Without the former “inspiration” how does one determine what to skills to master?

Or is it the idea that one evaluate the current market, determine what skills are currently valued and dedicate oneself to mastering them with the promise of eventual meaning and fulfilment?

I certainly like the idea of training up on valuable skills. What concerns me is that the work world skills are changing SO fast these days, that it is hard to decide which ones will be valuable long enough to master them.

Awesome summary of your books Cal! great!

Cal,

I love “So Good…” and it’s really changed my outlook on how I approach work and a career.

My question is this: what do you do when the thing you’ve built up career capital in… Isn’t something you want to have career capital in. I don’t like the idea of “mastering” my current craft, though I would LOVE to master “something…”

I’m a technical trainer currently, and have spent the last few years getting “good” at corporate training and such.

I love teaching people things… I hate teaching corporate stuff and “this is what you click on to do this” kinds of stuff… Yet it’s what’s led me to be successful in my work.

How do you reconcile this issue?

Thanks for your work.